How to build a context graph

@JayaGup10 and @ashugarg recently wrote about context graphs, the layer that captures decision traces rather than just data. The argument: the next trillion-dollar platforms won't be built by adding AI to existing systems of record, but by capturing the reasoning that connects data to action.

The piece resonated, and ever since then I’ve gotten a lot of questions about: how do you actually build one?

The answer isn’t “add memory to your agent” or wire up MCP. In fact, the word graph itself is a little misleading. What you’re really trying to model is far more dynamic and probabilistic than a static graph suggests.

The honest answer is that this is structurally hard. Not “scale up compute” hard — rethink your assumptions hard. Context graphs don’t exist today because building them forces us to confront problems we’ve spent decades ignoring.

Every organization pays a fragmentation tax: the cost of manually stitching together context that was never captured in the first place. Different functions use different tools, each with its own partial view of the same underlying reality. A context graph is infrastructure to stop paying that tax. But to build one, you first have to understand why the tax exists.

Three ideas shape how I think about this.

The Two Clocks Problem

There's an intuition that's helped me think about why this is difficult: we've built all our systems around only half of time.

Your CRM stores the final deal value, not the negotiation. Your ticket system stores "resolved," not the reasoning. Your codebase stores current state, not the two architectural debates that produced it.

We've built trillion-dollar infrastructure for what's true now. Almost nothing for why it became true.

This made sense when humans were the reasoning layer. The organizational brain was distributed across human heads, reconstructed on demand through conversation. Now we want AI systems to make decisions, and we've given them nothing to reason from. We're asking models to exercise judgment without access to precedent. It's like training a lawyer on verdicts without case law.

The config file says timeout=30s. It used to say timeout=5s. Someone tripled it. Why? The git blame shows who. The reasoning is gone.

This pattern is everywhere. The CRM says "closed lost." Doesn't say you were the second choice and the winner had one feature you're shipping next quarter. The treatment plan says "switched to Drug B." Doesn't say Drug A was working but insurance stopped covering it. The contract says 60-day termination clause. Doesn't say the client pushed for 30 and you traded it for the liability cap.

I call this the two clocks problem. Every system has a state clock—what's true right now—and an event clock—what happened, in what order, with what reasoning. We've built elaborate infrastructure for the state clock. The event clock barely exists.

State is easy. It's just a database. Events are hard because they're ephemeral—they happen and they're gone. State overwrites; events must append. And the most important part of the event clock—the reasoning connecting observations to actions—was never treated as data. It lived in heads, Slack threads, meetings that weren't recorded.

Three things make this hard:

- Most systems aren’t fully observable. Any real system has black boxes: legacy code, third-party services, emergent behavior across components. You can't capture reasoning about things you can't see.

- There's no universal ontology. Every organization has its own entities, relationships, semantics. "Customer" means something different at a B2B SaaS company than at a consumer marketplace. The context graph can't assume structure; it has to learn it.

- Everything is changing. The system you're modeling changes daily. You're not documenting a static reality, you're tracking change.

These problems interact. You're trying to reconstruct an event clock for a system you can only partially observe, whose structure you have to discover, and which is mutating underneath you.

Most "knowledge management" projects fail because they treat this as a static problem. Ingest documents, build a graph, query it later. But documents are just frozen state. The event clock requires capturing process, and process is dynamic.

So, how do you build an event clock for a system you can't fully see, can't fully schema, and can't hold still?

Agents As Informed Walkers

The ontology problem looks unsolvable at first. Every organization is different. Every system has unique structure. You can't standardize "how decisions work" any more than you can standardize "how companies work."

But there's something that navigates arbitrary systems by definition: agents.

When an agent works through a problem (investigating an issue, making a decision, completing a task) it figures out the relevant ontology on the fly. Which entities matter? How do they relate? What information do I need? What actions are available?

The agent's trajectory through the problem is a trace through state space. It's an implicit map of the ontology, discovered through use rather than specified upfront.

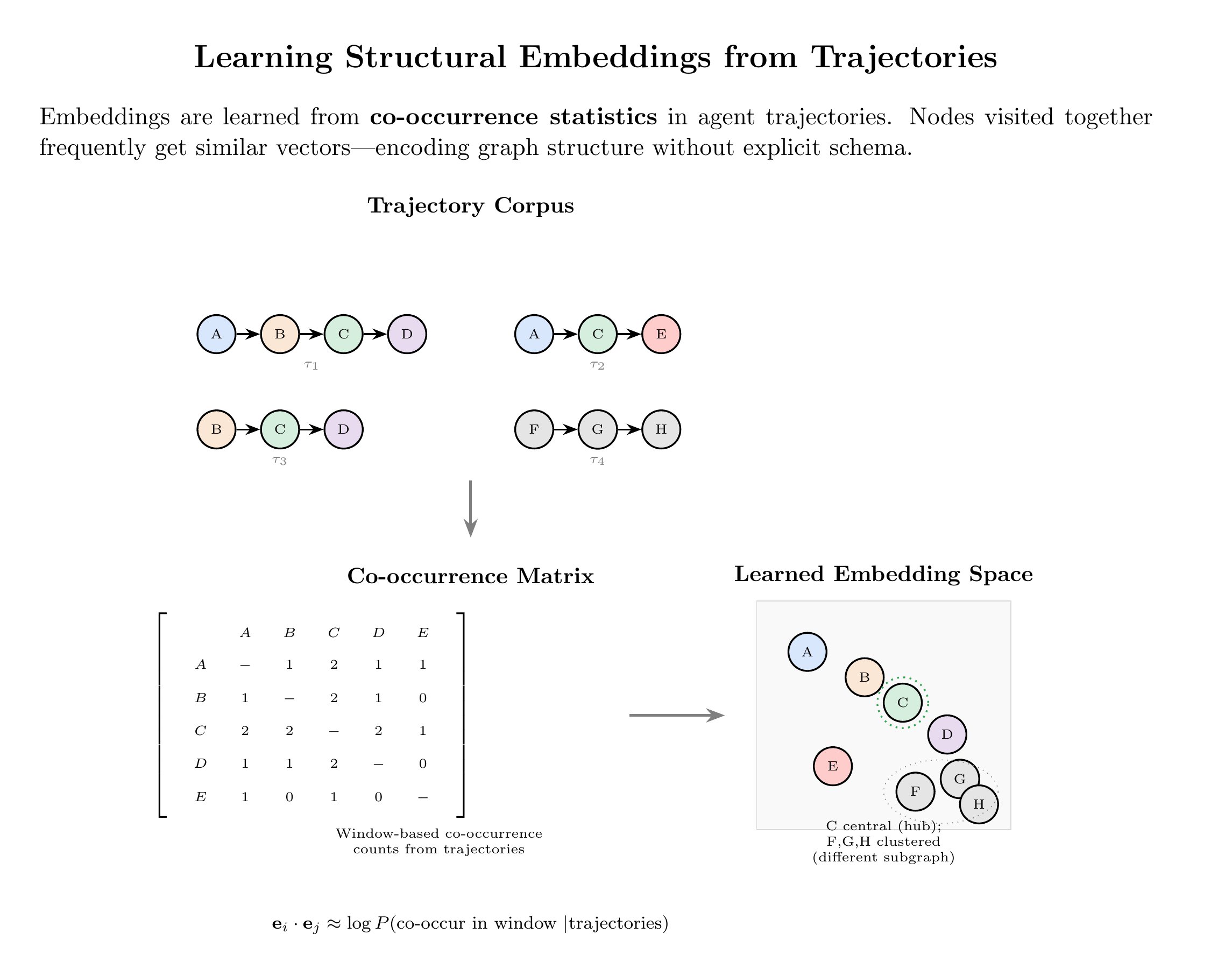

Typical embeddings are semantic: similar meanings, nearby vectors. That's useful for retrieval, not for what we need. We need embeddings that encode structure — not "these concepts mean similar things" but "these entities play similar roles" or "these events co-occur in decision chains."

Semantic embeddings encode meaning. Organizational reasoning requires us to model the structure and shape of decisions.

The information isn't about meaning. It's about the shapes of reasoning. Which entities get touched together when solving problems? Which events precede which? What are the traversal patterns through organizational state space?

There's an intuition from graph representation learning that’s helpful here. Graph embeddings (node2vec) showed you don't need to know graph structure to learn representations of it. Random walks—sequences of nodes visited by wandering through edges—are sufficient. Co-occurrence statistics encode structure. Nodes appearing together frequently are related, either directly connected or playing analogous roles in different neighborhoods.

This inverts the usual assumption. You don't need to understand a system to represent it. Traverse it enough times and the representation emerges. The schema isn't the starting point. It's the output.

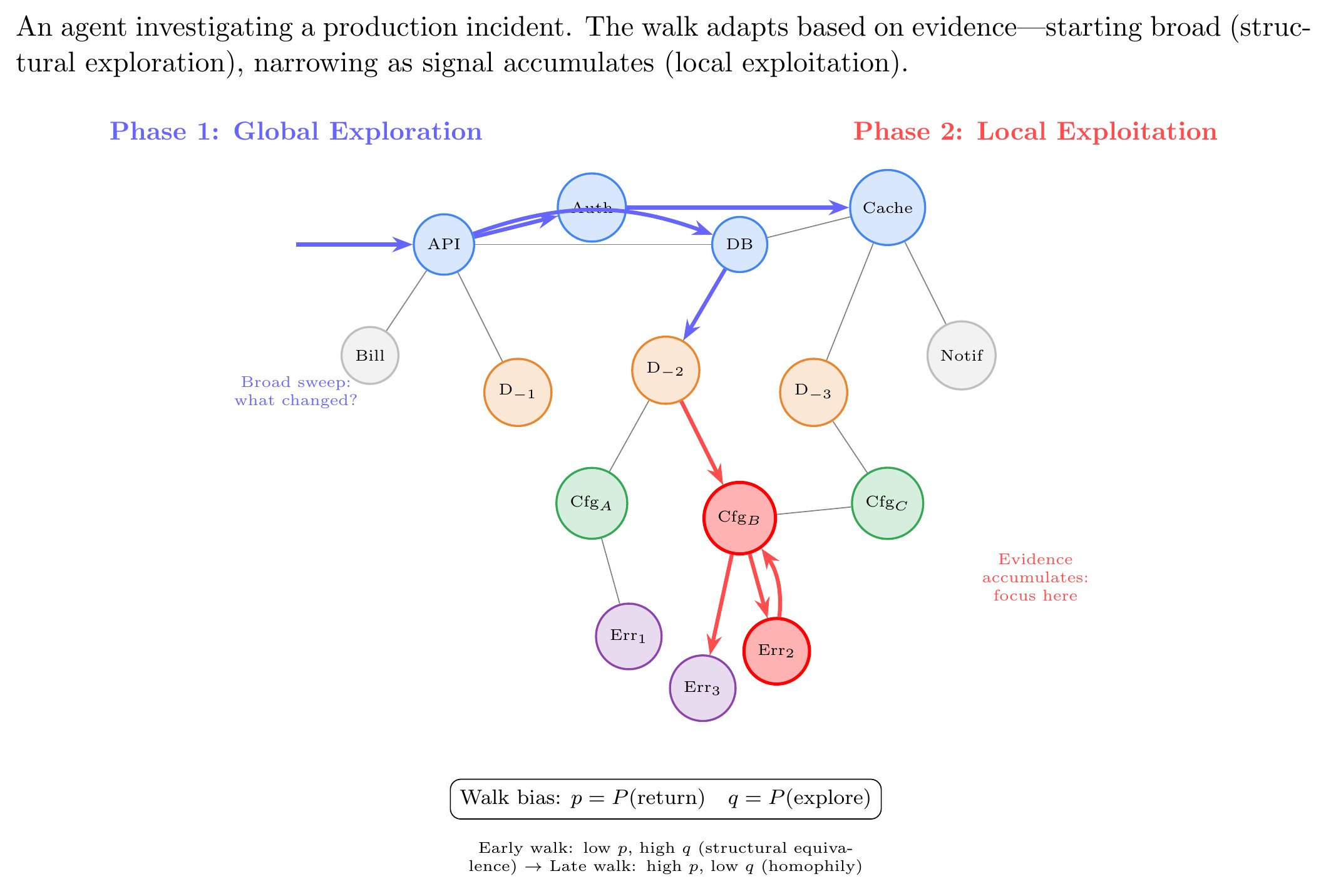

But the way you walk determines what you learn. Node2vec uses two parameters controlling walk bias. Local walks (likely to backtrack) learn homophily — nodes are similar because they're connected. Global walks (pushing outward) learn structural equivalence — nodes are similar because they play analogous roles, even if never directly connected.

Consider two senior engineers at a company. One works on payments, one on notifications. No shared tickets, no overlapping code, no common Slack channels. Homophily wouldn't see them as similar. But structurally they're equivalent—same role in different subgraphs, similar decision patterns, similar escalation paths. Structural equivalence reveals this.

Agents are informed (not random) walkers.

When an agent investigates an issue or completes a task, it traverses organizational state space. It touches systems, reads data, calls APIs. The trajectory is a walk through the graph of organizational entities.

Unlike random walks, agent trajectories are problem-directed. The agent adapts based on what it finds. Investigating a production incident, it might start broad—what changed recently across all systems? That's global exploration, structural equivalence territory. As evidence accumulates, it narrows to specific services, specific deployment history, specific request paths. That's local exploration, homophily territory.

Random walks discover structure through brute-force coverage. Informed walks discover structure through problem-directed coverage. The agent goes where the problem takes it, and problems reveal what actually matters.

Engineered correctly, agent trajectories become the event clock.

Each trajectory samples organizational structure, biased toward parts that matter for real work. Accumulate thousands and you get a learned representation of how the organization functions, discovered through use.

The ontology emerges from walks. Entities appearing repeatedly are entities that matter. Relationships traversed are relationships that are real. Structural equivalences reveal themselves when different agents solving different problems follow analogous paths.

There's economic elegance here. The agents aren't building the context graph—they're solving problems worth paying for. The context graph is the exhaust. Better context makes agents more capable, capable agents get deployed more, deployment generates trajectories, trajectories build context. But it only works if agents do work that justifies the compute.

Context Graphs Are Organizational World Models

There's a concept worth taking seriously because it reframes what context graphs actually are: world models.

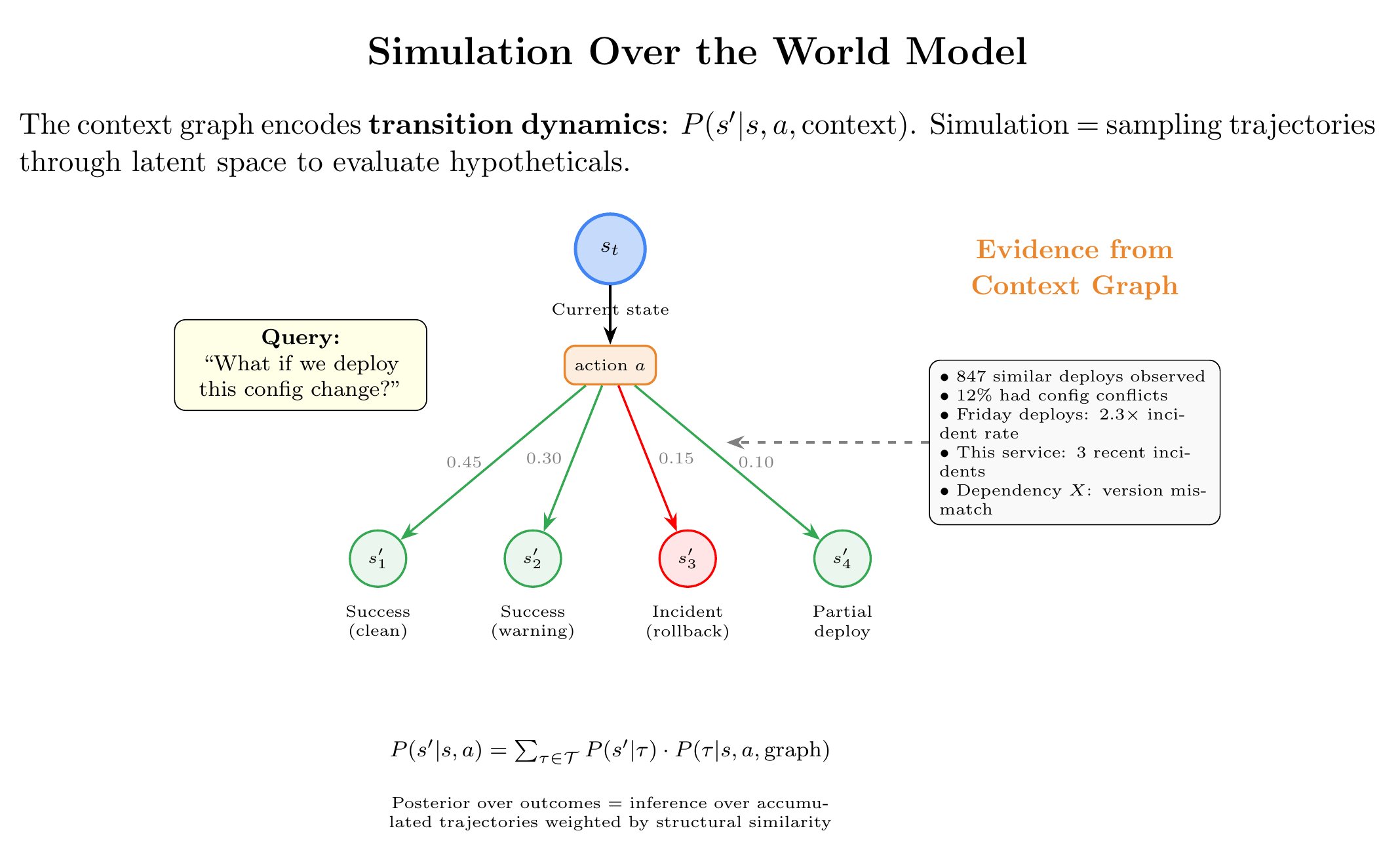

A world model is a learned, compressed representation of how an environment works. It encodes dynamics, ie. what happens when you take actions suspended in a specific state. It captures structure: what entities exist and how they relate. And it enables prediction: given a current state and a proposed action, what happens next?

World models demonstrate something important: agents can learn compressed representations of environments and train entirely inside "dreams"—simulated trajectories through latent space. The world model becomes a simulator. You can run hypotheticals and get useful answers without executing in the real environment.

This has an obvious analogy in robotics. A world model capturing physics (how objects fall, how forces propagate) lets you simulate robot actions before executing them, train policies in imagination, explore dangerous scenarios safely, and transfer to physical hardware. The better your physics model, the more useful your simulations.

The same logic applies to organizations, but the physics is different.

Organizational physics isn't mass and momentum. It's decision dynamics. How do exceptions get approved? How do escalations propagate? What happens when you change this configuration while that feature flag is enabled? What's the blast radius of deploying to this service given current dependency state?

State tells you what's true. The event clock tells you how the system behaves—and behavior is what you need to simulate.

A context graph with enough accumulated structure becomes a world model for organizational physics. It encodes how decisions unfold, how state changes propagate, how entities interact. Once you have that, you can simulate.

At PlayerZero, we build code simulations: projecting hypothetical changes onto our model of production systems and predicting outcomes. Given a proposed change, current configurations and feature flags, patterns of how users exercise the system: will this break something? What's the failure mode? Which customers get affected?

These simulations aren't magic. They're inference over accumulated structure. We've watched enough trajectories through production problems to learn patterns—which code paths are fragile, which configurations interact dangerously, which deployment sequences cause incidents. The world model encodes this. Simulation is querying the model with hypotheticals.

Simulation is the test of understanding. If your context graph can't answer "what if," it's just a search index.

There's a deeper implication for the continual learning debate.

Many folks argue AI isn't transforming the economy because models can't learn on the job—we're stuck building custom training loops for every capability, which doesn't scale to the long tail of organizational knowledge. He's right about the diagnosis.

But I think the standard framing is a distraction. Continual learning asks: how do we update weights from ongoing experience? That's hard—catastrophic forgetting, distributional shift, expensive retraining.

World models suggest an alternative: keep the model fixed, improve the world model it reasons over. The model doesn't need to learn if the world model keeps expanding.

This is what agents can do over accumulated context graphs. Each trajectory is evidence about organizational dynamics. At decision time, perform inference over this evidence: given everything captured about how this system behaves, given current observations, what's the posterior over what's happening? What actions succeed?

More trajectories, better inference. Not because the model updated, but because the world model expanded.

And because the world model supports simulation, you get something more powerful: counterfactual reasoning. Not just "what happened in similar situations?" but "what would happen if I took this action?" The agent imagines futures, evaluates them, chooses accordingly.

This is what experienced employees have that new hires don't. Not different cognitive architecture, a better world model. They've seen enough situations to simulate outcomes. "If we push this Friday, on-call will have a bad weekend." That's not retrieval. It's inference over an internal model of system behavior.

The path to economically transformative AI might not require solving continual learning. It might require building world models that let static models behave as if they're learning, through expanding evidence bases and inference-time compute to reason and simulate over them.

The model is the engine. The context graph is the world model that makes the engine useful.

What this means

Context graphs require solving three problems:

The two clocks problem. We've built trillion-dollar infrastructure for state and almost nothing for reasoning. The event clock has to be reconstructed.

Schema as output. You can't predefine organizational ontology. Agent trajectories discover structure through problem-directed traversal. The embeddings are structural, not semantic—capturing neighborhoods and reasoning patterns, not meaning.

World models, not retrieval systems. Context graphs that accumulate enough structure become simulators. They encode organizational physics—decision dynamics, state propagation, entity interactions. Simulation is the test. If you can ask "what if?" and get useful answers, you've built something real.

The companies that do this will have something qualitatively different. Not agents that complete tasks—organizational intelligence that compounds. That simulates futures, not just retrieves pasts. That reasons from learned world models rather than starting from scratch.

That's the unlock. Not better models. Better infrastructure for making deployed intelligence accumulate.